Sculptural Works

Collage Works

My father received a degree in aeronautical engineering at MIT in 1943. The Air Force moved him promptly to Cleveland to work on military aircraft design. He moved to the civilian side of the military/industrial complex when he moved to the United Technologies Research Laboratories in East Hartford in 1951, the year after I was born. He specialized in wind-tunnel engineering until he was promoted to an executive level to help run the Laboratory business until he retired in 1987.

My Aeronautical Series is about my Dad and the post-war American culture in which he lived his adult years. Using the metaphor of his connections to airplanes, each piece represents a different view of his life and culture from my perspective, starting from my childhood impressions and ending with his influence in my life today.

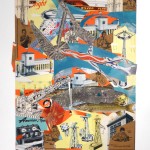

Collage #1: the A, B, C and D’s of Aeronautical Engineering

Dad had started at MIT with a major in mechanical engineering. In 1943 as part of the war effort he was obliged to shift his studies to the then nascent science of aeronautical engineering. During World War II and and on through the early years of the Cold War aeronautical engineering developed at an astonishingly rapid pace. As with its close cousin rocket science, it was renown for its complexity, excitement, and the open-ended possibilities for the future, both for good and evil.

The emergence of aeronautical engineering starts with man’s ancient dream to fly as a bird, represented in this collage by the bird sitting on the statue of Darius the Great. Centuries of advances in building technologies and mathematics culminated in Wright brothers flight in 1903, just 18 years before Dad was born. Propeller-driven aerodynamically contoured airplanes developed rapidly in the years proceeding the war. Within just a few years of Dad’s graduation from MIT he was designing jet-propelled aircraft. American military hegemony depended on its ability to design and manufacture the world’s best airplanes. Darius could only dream of such a power over his enemies.

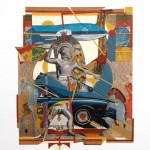

Collage #2: The Aeronautical Warrior King

On the one day a year when the families of the Laboratory employees were allowed into the otherwise secure facility, Dad walked me through the main wind tunnel. It had a huge diameter at one end, perhaps as much as 20′ across. All of that diameter funneled down to a tiny throat where Dad placed model airplanes for empirical measurements of one or another refinements of an aeronautical design. That wind tunnel was the most amazing structure I had seen to that point. That DAD RAN THAT MACHINE was etched on my consciousness. Dad also had a home workshop where he was always building things, including toys. I still have the rocking horse he built for me for the Christmas of 1952. This collage is a homage to Dad’s ability to build things. The American economy of the post-war years was based on the manufacture of a vast number of products, including the commercial production of magnificent sleek machines for transportation. The Warrior King’s steed is a Buick Riviera; his Crown is a KLM Boeing 747.

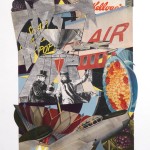

Collage #3: Kitchen-made Fighter Aircraft Drone

Beyond the confines of his workshop Dad was also handy around the house. He even cooked breakfast now and then. Food in post-war America became a manufactured and marketed product. Madison Avenue promoted the mush of Spam with geometric precision: a sliced spiral progression of rounded rectangles or a square rectangular solid with a textured diagonal grid on its top. Images of American abundance and leisure sold hot dogs, another formless meat product like Spam that was packaged with geometric clarity. Advertisements showed the ease with which the application of heat, butter and recipe-guided technique could transform packed mixes of food ingredients into perfectly circular pancakes and seductively curved buns.

Dad never lived to see the profusion of drones currently populating the sky above us. They have become an easily acquired consumer product. Now every man can create his own Air Force. This collage imagines a recipe for making fighter aircraft drones in one’s own kitchen, much as Dad years ago could make pancakes fly off the frying pan. When everyone has a 3D printer on their kitchen counter, that will be possible. Just add batteries and open the kitchen window…

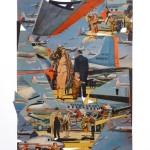

Collage #4: American Aeronautical

Dad flew on commercial aircraft frequently for business. He brought me back postcards from each of the more than 30 states he visited. I toured the United States vicariously through those postcards. The airline transportation system grew exponentially during the post-war period, as implied by the profusion of aircraft in these vintage American Airlines advertisements. Airplane travel was then glamorous, daring and sexy. One descended from airplanes via stairs and paraded in full view across the tarmac to the terminal, a moment of celebrity for which everyone dressed in their best clothes!

Collage #5: Atomic Aeronautical

The Cold War overshadowed the young years of everyone of my generation. Aeronautical engineers, including my Dad, designed the bombers that became the prime delivery system for the America’s nuclear arsenal. This collage depicts man’s fascination with conquest and the fruits of war, from ancient times onward. The black-and-white photograph is from Mussolini’s room-size model of Ancient Rome. It shows the emperor’s palace on the Palatine Hill and the adjacent Circus Maximus, the ultimate ancient playground for war games. The strawberry jam on the boy’s face suggests the naïveté that prevailed among many atomic warriors of that era that nuclear war was winnable, albeit a bit messy.

Collage #6: Krispy Aeronautical

Dad lived long enough to witness the beginning of the decline of America. The projection of its military might became overextended in Vietnam and other distant wars. The ballooning riches of the consumer economy, puffed up with the hot air of advertising, no longer soared. The slogan “snap, crackle and pop” that once enthusiastically promoted Rice Krispies became, with the growing realization of the nutritional vacuousness of that product, an apt ironic summation for of the state of American culture.

Collage #7: Biographical Aeronautical

I remember clipping this airplane image from a magazine 40 years ago, roughly when the American airline industry was at its healthiest point. It was an advertisement for the now-defunct Braniff International Airways. Braniff commissioned American artist Alexander Calder to paint two plane liveries in the mid 1970’s. This second red/white/blue design commemorated the forthcoming USA Bicentennial. Calder was renown for his “mobiles”, kinetic forms suspended by wire from structural armatures. The airplanes, finished just a year before his death, were not only his largest mobiles, but also the only ones that could fly free of any supporting wire and armatures.

In his college years Calder, like my Dad, studied mechanical engineering. He worked for awhile as a hydraulic engineer and draftsman before enrolling in the Art Students’ League in New York. In 1926 at the age of 28 he moved to Paris, where he met many leading avant-garde artists including Mondrian, Miro, Arp and Duchamp. At the suggestion of a Parisian toy merchant, Calder began making toys from found objects. Back in the US in 1927 he designed several kinetic children’s toys that were mass-produced. His fascination with toys lasted for the rest of his life, as did his love for Paris. For the last dozen years of his life his main art studio was located in the country southwest of Paris. Calder died unexpectedly shortly after the opening of a major retrospective of his work at the Whitney Museum. Surrounded by his lifetime’s production of sculpture, painting, jewelry and tapestry, the centerpiece of the show was his “Cirque Calder”, composed from toys he had made during his first magical year in Paris.

Besides the image of the airplane and the aerial photographs of Manhattan and Paris, most of the other images in the collage come from old catalogues for Erector Sets and American Flyer Trains. Both toys were manufactured in New Haven by the A. C. Gilbert Company. Dad gave both toys to me in the 1950’s. The main sales venue for Gilbert toys was in an unusual 6-story building that A. C. Gilbert built for that purpose in New York on 25th St. between 5th and Broadway. The Erector Set that Dad gave to me was the one my Grandfather gave to him in the 1930’s. I know my Grandfather brought Dad to New York for a visit in the 1930’s. Very possibly his Erector Set was purchased at that 25th Street building. That building, an old photo of which begins the progression of collage vignettes, still exists just a few blocks from my current home and workshop.

This final collage in this Aeronautical Series suggests through the metaphor of Calder’s biography how Dad’s love for building airplanes and for building things in general lives on years after his death in my own life. After retiring from a long career as a architect, I now play daily in my workshop, making sculptures that appear to be toy machines. Many of those sculptures contain Erector Set pieces, pieces from Dad’s set and from the dozens of additional sets I have purchased on eBay in recent years.